As a term for describing a

basic unit of Urhobo culture, the

word “clan” came into existence at the onset of British colonial rule

in

Urhoboland in the beginning decades of the 20th century.

From

prehistoric times, and even during that era of colonial rule, the

Urhobo people

employed their own native expressions, including ẹkpotọ (that is, ẹkpo

r’

otọ in full phrasing), to describe these units of Urhobo

culture.

Other words that were so used to describe Urhobo’s cultural units were ẹkuotọ and ubrotọ. However, that colonial

term of “clans” dominated Urhobo studies and everyday analysis of

Urhobo ways

of life until its authority was undermined in the late 1990s.

Its current rival term of “kingdom” was first applied to the special case of Okpe by Onigu Otite in his 1969 Ph.D. thesis for London University, which has since been published as Autonomy and Dependence: The Urhobo Kingdom of Okpe in Modern Nigeria (1973). Otite’s academic use of the term “kingdom” was specialized and was largely circumscribed by the unique events of Okpe history. The publication of Otite’s book in the early 1970s did not diminish the use of the term “clans” for describing Urhobo’s subcultures nor did it lead to any upswing in the use of “kingdoms” in Urhobo studies and everyday life.

Today, the term “clan” has largely been swept off Urhobo political vocabulary. However, it is uncertain whether “kingdoms” has effectively replaced the British term “clans” or indeed traditional indigenous Urhobo terms, such as ẹkpotọ, for which the British had coined the word “clans” a century ago. Indeed, this note of disquiet may well be phrased differently, as a query: Is it possible that the introduction of “kingdoms” has done more harm to Urhobo’s cultural circumstances than any appearance of prestige that it has bestowed on our royal institutions? What one can say with some certainty is that there is considerable confusion in the usages and meanings of “kingdoms” in modern Urhobo cultural life. Certainly, the term “kingdoms” has left out of its semantic sway whole areas of culture that are of traditional concern to the Urhobo people. Into this deepening confusion has now strolled the Delta State Government waiving what appears to be an all-embracing new claim that it has an inherent power to decree Urhobo “kingdoms” into existence by way of government gazettes. Without a doubt, a dark cloud of cultural crisis now hangs over the Urhobo horizon. In these circumstances, there is need to clarify the historical and cultural meanings of “clans” and “kingdoms.” To be silent and allow this confusion to be waged in ignorance serves no one well – not Urhobo culture, not the Delta State Government, and certainly not Urhobo chieftains.

Before I proceed any further with this analysis, I want to make a point abundantly clear. This paper is not intended to defend the British colonial term “clans” or to attack its putative rival “kingdoms.” On the contrary, it is to invite an engaging conversation on a vital aspect of Urhobo history and culture which is currently under distress. Urhobo culture is ours and we must not allow it to flounder.

Pre-Historic

Origins of Urhobo Cultural Units

For now, permit me to put aside the two controversial terms of “clans” and “kingdoms.” In their place, I will use the politically neutral expression of “Urhobo Cultural Units” or more simply “Urhobo’s Subcultures.” These are sociological notions for which the word “clans” or “kingdoms” had been suggested as a shorthand. Note that I have not employed another popular expression, polities, in characterizing these subunits of Urhobo culture. That is because the word polities is limited by its political anthropological baggage to matters political whereas the units of Urhobo culture that are the subject of our discussion here have vast historical and cultural nuances and interpretations.

These basic subunits of Urhobo culture were prehistoric. That is, their existence predated modern historiography that assigns dates and ascertainable time periods to historical events. Today, Urhobo scholars and culture artists have arrived at a sum total of twenty-two of these units of Urhobo culture. By saying that they are prehistoric, we mean to say that all of them -- Agbarha-Ame, Agbarha Otor, Agbarho, Agbon, Arhavwarien, Avwraka, Ephron, Evwreni, Eghwu, Idjerhe, Oghara, Ogor, Okere, Okparebe, Okpe, Olomu, Orogun, Udu, Ughelli, Ughievwen, Uvwie, and Uwherun – were well settled before the rise of significant historical epochs that defined the boundaries of medieval and modern Urhobo history. Thus, it is presumed that all these twenty-two subunits of Urhobo culture were in existence before the rise of Benin Empire in the 1440s and before the arrival of the Portuguese in the Western Niger Delta in the 1480s.

To say that Urhobo’s subcultures were ancient and prehistoric is not to suggest that they are of the same age and generation. On the contrary, a group of these subcultures was of great antiquity, giving birth to newer subcultures. In general, the older subcultures were geographically separated from the less ancient ones. There is ample evidence from internal Urhobo folk knowledge and rituals that suggests that the oldest cultural subunits of Urhoboland are in the low-lying swampy southeastern region which is bounded by Patani River and Ijawland in the south and Isokoland in the east. These primeval subcultures of Urhoboland include Uwherun, Evwreni, Arhavwarien, Okparebe, Eghwu, and Olomu.

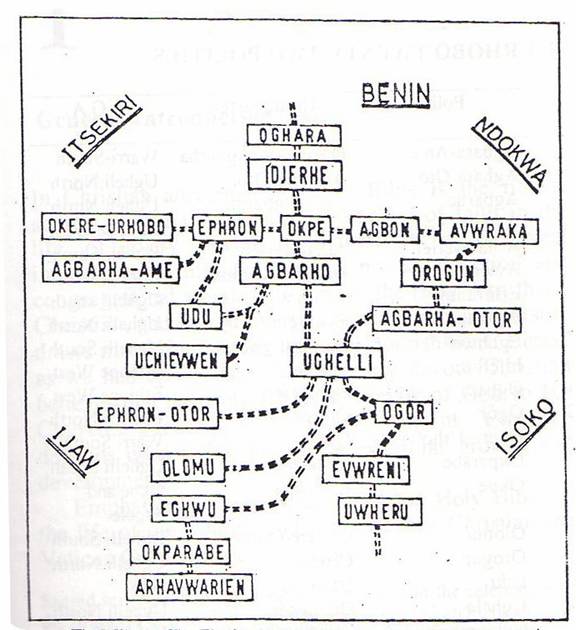

Figure

1.1

Michael Nabofa’s Geographical Display of Urhobo’s Cultural Units

It is noteworthy that in precolonial times, Iyede in modern Isoko was counted among the earliest subcultures of Urhoboland. It has since been re-assigned to Isoko, suggesting that the cultural walls that separate Urhobo from Isoko are thin.4 The migrations into Urhoboland that are variously claimed to have occurred, with points of origin in lands once ruled by the Ogiso dynasty in areas now named Benin, most probably followed the creeks into this swampy region of southeastern Urhoboland and Isokoland; rather than through the impenetrable rainforests of northwestern Urhoboland.

Urhobo's Subcultures and the

Conquest of Western Niger Delta’s Rainforests

Urhobo folk

history suggests that it was from the

swampy southeastern Urhobo region that the conquest of the bigger and

more

ample rainforests of northwestern Urhoboland was launched and

accomplished.

Those who achieved this extraordinary feat of conquest were fresh units

who

founded new sub-cultures in areas that they conquered, spreading Urhobo

language and culture across these virgin tropical rainforests. Some of

these

sub-cultures were established in groups. Thus, the so-called Oghwoghwa

Cultural Group (see Erivwo:

2003: 109-113) -- consisting of Ogor, Ughelli, Agbarha-Otor, and Orogun

–

probably launched their campaign in tandem, occupying contiguous vital

lands in

the rainforests of the Western Niger Delta. Other groups went farther

away from

the southeast homeland. Thus, having followed similar paths from Isoko

(in the

case of Agbon) and Erhowa (in modern Isoko, in the case of Okpe)) and

having

both registered settlements in Olomu in southeastern Urhobo, the

ancestors of

the Okpe people and of Agbon conquered and claimed vital territories

closer to

River Ethiope.

Another genre of campaign of expansion of territory by a group of Urhobo sub-cultures in the rainforests of the Western Niger Delta is noteworthy. Just as Olomu proved to be a fertile starting point and a gateway for secondary groups of sub-cultures for campaigns of conquests of large portions of rainforests of the Western Niger Delta, so has Agbarha-Otor turned out to be a veritable cradle in breeding new tertiary sub-cultures. It was from Agbarha-Otor that groups left to found Agbarha-Ame, in modern Warri, naming their subculture after their ancestral land as Agbarha. Then an even more arduous campaign was waged when two separate groups of Agbarha-Otor migrants crossed the River Ethiope and occupied virgin rainforests on the Western side of an untamed river. They named their new sub-cultures after their ancestral towns in Agbarha-Otor as Idjerhe and Oghara.

Historic Significance of the Conquest of

Western Niger Delta’s Rainforests by Urhobo Cultural Units

It is probably unnecessary

at this point of our analysis to

attempt a blow-by-blow account of the founding of the twenty-two

sub-groups of

Urhobo culture. But it is important that we attach some significance to

the above

statement of the groups of founding subcultures that are now more

controversially labeled as “clans” or “kingdoms.”

Modern Urhobos correctly boast that they represent the largest group in the Western Niger Delta. Moreover, Urhobo occupies a sizeable chunk of the dry lands of the Western Niger Delta. All these we owe to those whose courage and heroism enabled the Urhobo to occupy prime rainforests. We must not forget that we shared the same rainforests with the Isoko and the Ukwuani. That our share of these lands is enviable owes everything to the fact that our prehistoric ancestors were able to conquer them.

“Conquest” is an evocative term in historical scholarship. Conquerors often subdue their own people and then overcome others. Such conquerors of peoples are frequently crowned as kings. But the conquest upon which our ancestors embarked was of a different type. It was the conquest of an untamed and unoccupied rainforest that was deemed to be dangerous. Today, we cannot imagine how fearsome these lands were in their pristine form. They had wild animals in abundance. That they are all gone from our territory is probably due to the fact that part of the responsibility of our founding ancestors was to destroy wild animals. It is said that Evwreni was founded by a group of hunters who were hired by Iyede to kill menacing elephants. Elephants (eni in Urhobo), lions (okpohrokpo), tigers (ẹdjẹnẹkpo), gorillas (ọsia), and hippotemuses (ẹrhẹ) have all gone from our lands, but they were once here in Urhoboland in some abundance.

There is another point of significance to be stressed. Apart from the fact that the secondary and tertiary subcultures of northwestern Urhoboland have larger territories than those in the low-lying swampy southeast, it is noteworthy that -- with the remarkable exception of Olomu -- these primeval subcultures of the southeast are almost all single-town cultures. In contrast, the larger secondary and tertiary subcultures of the northwest are multiple-town cultures. The multiplicities of towns and villages in these cultures – in Ughelli, Agbarha-Otor, Orogun, Okpe, Agbon, Agbarho, Idjerhe, etc. – are striking. Such multiplication of settlements of towns and villages within each subculture enabled the conquest and occupation of as much territory as was accomplished in these lands that were once untamed.

Properties and

Characteristics of Cultural Units of Urhoboland

These subcultures of

Urhobo have borne the burden of Urhobo

history. They also carry the weight of Urhobo culture and its political

organisation.

Together, they all bear certain markers and characteristics that set

Urhobo and

its people apart from other cultures and peoples. So that we may be

sure that

these subcultures define what Urhobo is, we should map out their

properties and

characteristics.

(i) Territory

with Boundaries and Integrity

Every Urhobo subculture

has a

territory that has boundaries with other sub-cultures and occasionally

with

non-Urhobo cultural entities, such as the Isoko, Ijaw, and Ukwuani. A

unique aspect

of Urhoboland is that the Urhobo people were the first to occupy their

own

portions in the hinterland of the rainforests of Western Niger Delta.

In most

instances, therefore, bearers of each subculture of Urhobo occupy

territory

that their ancestors were the first to conquer and occupy. This

attribute of

Urhobo’s subcultures has imparted a sense of collective ownership of

the

territories of these units of Urhobo culture. The integrity of each of

Urhobo’s

subcultures derives from its ownership of its own territory that it has

conquered and occupied through its own exploits.

(ii) Sub-Cultural

Headquarters

and

Eponymous

Ancestral

Shrines

Each subculture has its

own

headquarters. It is usually located in the first place in which the

founding

ancestors settled. These headquarters have eponymous ancestral shrines,

venerating the spirits of the founding ancestors whose names are

associated

with the entire subculture.

It

is noteworthy that the high regard for these ancestral shrines is

shared across

all communities, including Christian families. In effect, these

eponymous

ancestral shrines are regarded as historic institutions.

(iii) Endowment

of

Individual’s

Identity

as an Urhobo Person

Every

person who claims to be Urhobo does so only through his or her

membership of a

subculture or subcultures as their father’s or mother’s birth right. No

one can

claim to be Urhobo directly, without belonging to a subculture or

subcultures

of Urhobo. This attribute carries with it the claim of certain rights

from members

of the subculture who are expected to work for the survival and

improvement of

the entire subculture. But it is an attribute that also imposes

important

responsibilities on the subculture in its relationship to individual

members.

Until recent times, protection of the individual and care for his

remains after

death were responsibilities of the subculture or its further divisions.

(iv) Totems

and

Taboos

of

Sub-Cultures

For

the sake of maintaining the spiritual welfare of its members, some

subcultures

instituted their own set of totems and taboos whose observance would be

binding

on their communities. The power of totems instituted by Ughelli and

Orogun –

even over those of their members who are now converted to Christianity

– is

legendary. Other sub-cultures have similar regimes of totems.

(v) Sub-Cultural

Control

of

Urhobo’s

Linguistic Dialects

In the realm of language, Urhobo is a land of

great dialectic variability. Remarkably, each subculture has its own

dialect of

the Urhobo language. Native speakers of the Urhobo language can easily

tell

from what sub-culture a speaker of the Urhobo language hails.

(vi) Urhobo

Sub-cultures

and

the

Institution of King (Ovie)

One

of the most powerful cultural tools that each of Urhobo’s subcultures

has (or

had) at its disposal was the institution of kingship. Called Ovie

throughout Urhobo culture, an Urhobo king exists only at the

sub-cultural

level. Each subculture controls the rules that govern the ascension to

the subculture’s

throne. More importantly, each subculture could decide to exercise its

right to

have a king or not to have one. However, by common Urhobo usage, no

subculture

is allowed to have more than one Ovie at a time.5

It is noteworthy that until the explosion of royal institutions began in the 1950s, from instigation from various Nigerian governments, only a handful of Urhobo’s sub-cultures exercised their inherent rights to have kings. Ogor and Ughelli had stable regimes of kingship for a good portion – but by no means all – of their history. The Okpe had an historic instance of monarchy that went awry and thereafter the Okpe were reluctant to revive the institution, until 1945, centuries afterwards. The Agbon people chose for centuries of their history to make do with the maxim Okpako r’ Agbon oy’ Ovie r’ Agbon – meaning, Agbon sub-culture’s eldest is its King. Many other attitudes toward royal institutions emanated from the other subcultures of Urhoboland. The point is, it was their right to determine whether they wanted a king and if so on what terms.

(vii) An

Axiom of Co-Equality among Urhobo Sub-Cultures

There

is an underlying axiom in the relations among the units of Urhobo

culture. It

is that they are co-equal. For instance, although Okpe and Agbon are

each many

times larger in land and population than most of the Urhobo subcultures

of the

southeast, they cannot claim to be culturally superior to the much

smaller

sub-cultural units of southeast Urhoboland, such as Okparebe and

Arhavwarien.

British

Colonial Rule and the Naming of Urhobo’s Sub-Cultures as Clans

British

colonial rule

in Urhoboland began effectively in the first decade of the 20th

century, following a delay lasting many years (1894-1899) on account of

a

dispute between the Royal Niger Company and agents of the Niger Coast

Protectorate Government over what British interest had administrative

jurisdiction in Urhoboland (see Salubi 1958). When British colonial

rule

commenced, it was clear that the British had little knowledge of Urhobo

culture. This was largely because missionaries had not been as active

in the

Western Niger Delta as they had been elsewhere, say in Yorubaland and

Igboland

(see Ekeh 2005).

The British made up for lost ground in their understanding of Urhobo culture by relying heavily on “intelligence reports” provided by colonial administrative officers. For centuries, Europeans, including the British, relied on Atlantic coastal peoples for their information on the Urhobo. As it turned out, much of that information was either wrong or outright mischievous.6 Now, the colonial administrators’ intelligence reports sought to paint a correct picture of Urhobo ethnography. These efforts led the British to conclude that Urhobo culture was essentially based on a clan system. They identified the units that we have been calling Urhobo’s subcultures along with many of their properties that we described above.

How did the British colonial officers come up with the word “clans” to describe these subcultures of Urhoboland? By the early 1900s and 1910s, when the label was applied, Colonial Social Anthropology was not mature enough to be helpful to colonial officers in their efforts at understanding such entities as Urhobo. It is more likely that the label was picked up from Scottish history of Clans. In many ways, Urhobo sub-cultures were very much like ancient Scottish clans.

Urhobo

Reactions to British Colonial Ethnography of Urhoboland

As can be

imagined,

Urhobos were the principal informants for those who composed the

intelligence

reports. These reports were of course not made public, but key

decisions were

made on the strength of the information provided in them. It was

therefore the

British policies, apparently based on the intelligence reports, which

the

Urhobo people could judge. While accepting and even appreciating many

administrative policies of the British Colonial Government, a good

number of

them were rejected by the Urhobo people who fought against their

implementation

and indeed for their reversal.

Two instances will illustrate the point. The British wrongly assigned Orogun and Avwraka (which they misnamed as Abraka) to Kuale [that is, Ukwuani] Division in Warri Province for administrative purposes. Similarly, Idjerhe (misnamed Jesse by the British) was assigned to Benin Division in Benin Province for administration. The Urhobo people did not like these decisions and fought hard for their return from what they saw as their perverse allocation. All three of them were eventually returned to the Urhobo fold by being regrouped in administrative units that consisted entirely of Urhobo sub-cultures.

Urhobo Progress Union arose in the 1930s as a vehicle for conveying Urhobo concerns to the British Colonial Government. One of the first public responsibilities of Urhobo Progress Union was to convey Urhobo’s objection on the wrong rendering of their name to the British. Urhobos objected to unacceptable names given by the British to Urhobo and its sub-units, obviously owing to pronunciation problems that the British encountered with complicated Urhobo names. Thus, the British had difficulties with the “rh” in Urhobo. They simplified it, changing “Urh” to S” and thus yielding “Sobo,” a name that Urhobos found offensive.7 Urhobo Progress Union fought very hard to change Urhobo’s spoilt name and it succeeded when the British made a correction in a Gazette of October 1, 1938. Urhobo Progress Union was itself involved in making changes in its own sphere, changing its name from its previous version of Urhobo Progressive Union in the late 1930s.

We have pointed to these Urhobo reactions in order to highlight the point that the Urhobo people were not unaware of what the British were doing with their cultural institutions. Urhobo Progress Union certainly knew of the label “Clans” which the British used to describe Urhobo’s sub-cultures. It had no objection. Indeed, UPU employed the term clans in its official duties of working for Urhobo progress. Right up until the mid-1960s, when UPU was in its high phase of activities on behalf of the Urhobo people, it used the term clans frequently. Thus, in his 1965 address to the General Council of Urhobo Progress Union, the President-General of the Union, Chief T. E. A. Salubi, referred to the role of the clans in spreading development in Urhoboland, as follows:

I would love to hope,

indeed expect,

that the degree of oneness and unity so transparently exhibited at

Sapele on

the occasion [of Urhobo National Day Celebration] will diffuse down to

our

different clan areas and be

reflected in our ordinary life and day-to-day dealings with one another

in our

towns and villages (Salubi 1965, emphasis added).

It should be added that Nigerian nationalist scholars, including especially historians, objected to the use of such anthropological terms as tribes and clans, considering them to be derogatory and offensive. However, the general rejection of “clans” was from outside Urhoboland. The much preferred term of “kingdoms” did not catch up with Urhobo nationalist sentiments until the late 1990s!

Nigerian

Governments’ Interactions with Urhobo’s Sub-Cultures

Various

Nigerian

Governments, at the Regional and State levels particularly, which

followed

British Colonial Government, have also dealt with the significance of

these

sub-cultural entities that the British labelled as clans of Urhoboland.

It is

fair to say that most Nigerian Governments have accepted and respected

the fact

that Urhobo is in essence a confederation of twenty-two sub-cultures

whose

bases and roots are ancient and prehistoric. Until the bizarre incident

of 2006

in which Delta State Government sought to split an Urhobo sub-cultural

unit

into two, all previous Nigerian Governments had respected the integrity

of each

of the twenty-two units of Urhobo culture. Before dealing with the

abnormality

of that 2006 legislative episode by the Delta State Government that

clearly

violated the creed of Urhobo history and culture, it will be helpful to

sketch

how various previous generations of Nigerian governments, responded to

Urhobo’s

cultural system. Such an outline will probably help us all to see why

the 2006

legislative affront on Urhobo history and culture is so remarkably

different

from the conduct of previous Nigerian Governments.

How Western Nigerian Government

Dealt with

Action Group’s Difficulties with the Urhobo People

The first

Nigerian

Government which the Urhobo had to deal with was led by the Action

Group party

of Western Nigeria, from 1952 to

1964.

Unfortunately, Urhobos had a major problem with the Action Group and

its

leader, Chief Obafemi Awolowo, concerning the dispute on the title of

the King

of Itsekiri and the ownership of the city of Warri (see Edevbie 2007). The

Urhobo’s

response was an uncompromising and consistent rejection of the Action

Group at

the electoral polls. At a time when voting counted, the Urhobo’s

antipathy

towards the Action Group was hurtful for a party that lacked a clear

majority

in the Western House of Assembly. No amount of punishment of the Urhobo

worked

to persuade them to switch to the Action Group in their political

preferences.

The Action Group did its utmost to insinuate itself into Urhobo political affairs. Its bluntest tool was invocation of a property of Urhobo sub-culture. It is that every sub-culture was entitled to have an Ovie. It so happened that in the 1950s few of Urhobo’s sub-cultures had their own Ivie. The Action Group Government therefore orchestrated the selection of candidates for the throne of Ovie in each sub-culture where there was no seating Ovie. The Action Group supported its own candidates for these thrones.

Although this ploy did not work in convincing Urhobos to vote for the Action Group at the polls, it opened up a new chapter in Urhobo history. Playing within the logic of Urhobo culture that allocated the right of kingship to its sub-cultures, it nonetheless expanded Urhobo’s royal institutions well beyond what the Urhobos themselves wanted. One reason why many sub-cultures of Urhobo neglected to exercise their right to have a king was that it was costly to maintain an Ovie. Now, members of the new class of Ivie were more dependent on Government subsidies than on their own people, opening up new dynamics in Urhobo public affairs.

Mid-West

Government and Ordered Selection of Ivie

By the time

the

Mid-West Region was carved out of the Western Region in 1964, it was

very well

established that kingship was mandatory in Urhobo sub-cultures, still

then

called clans. What the Ministry of Chieftaincy Affairs sought to do was

to

bring order to the selection of the Ovie of each sub-culture. Urhobo

chieftains

seemed to have warmed up to the idea of this widespread kingship,

hoping that

it was one way of gaining sponsorship from the Government.

Two facts followed from this inordinate expansion of royal institutions in Urhoboland. The first is that the resulting Ivie were now ever more dependent on the Government. But their sheer numbers meant that they could not be as well cared for as if they were fewer. The other fact is that the kings became less dependent on their own people. These are dynamics that were liable to affect an institution that was invented from the necessity and imperatives of survival in a dangerous rainforest. It was no longer quite clear what the functions of the Ivie were. No doubt, many Government functionaries saw them as agents of the Government.

Whatever views one holds of the institution of Ovie, the Government had come to play a major role in moulding its place and functions in Urhobo culture. The catastrophic events of the 2006 legislation that sought to create an Urhobo sub-culture from the thin pages of a Government Gazette probably represent the ultimate in the unintended consequences of Government take-over of an ancient Urhobo convention. But before we examine that notorious event, we must first weigh the semantic changes that occurred in the characterization of units of Urhobo culture.

Renaming

Urhobo’s Sub-cultures as Kingdoms

There is a

measure of

trivialization that has recently crept into the naming of Urhobo

institutions

as they are rendered in a culturally alien English language. For an

Urhobo --

particularly for an Ughelli person -- there is an emotional difference

between

saying: “Ovie r’ Ughele” (in Urhobo)

or “Ovie of Ughelli” (in English).

The trivialization gets worse, along with the rather serious

grammatical

infraction that should be evident, in a new popular rendering in

English of the

same appellation: “Ovie of Ughelli

Kingdom."8

The infatuation with this new-found word “kingdom” descends down the

chain of

the modern Urhobo aristocracy. To give an example from another

sub-culture of

Urhoboland: In his exemplary curriculum vitae, which was crafted some

time in

the early 1980s, Chief T. E. A. Salubi cites one of his most valued

titles as “Okakuro of Agbon.” Since the late

1990s, the same title is now cited by its holders as “Okakuro

of

Agbon

Kingdom."9

Such banality of language regarding aristocratic titles in recent times has arisen from the introduction of the English word “kingdom” into modern Urhobo culture. Its rampant and gratuitous use has caused several problems for our understanding of Urhobo institutions. First, “kingdom” is virtually untranslatable into Urhobo language. Second, it has been used as a replacement – that is, supposedly, as the synonym -- for the English word “clan.” Remember that “clan” was introduced into Urhobo by British colonial administrators as a way of characterizing Urhobo’s sub-cultures.

The origin of this new usage of “kingdom” has been traced to HRH Adjara III and Andy Omokri’s (1997) Urhobo Kingdoms: Political and Social Systems. This is how the late Professor F. M. A. Ukoli sketched the rise of the term “kingdoms” in modern Urhobo culture:

The Urhobo constitute an

ethnic

group, but there is great diversity in the origins of the various clans

as well

as diversity in their culture. Indeed, the differences are so marked

that H.R.H

Adjara III and Omokri, in their recent book Urhobo

Kingdoms, elevate the 22 clans which constitute the entire Urhobo

tribe to

the status of kingdoms (Ukoli 2007: 647).

Remarkably, Adjara III and Omokri did not discard the term clan in their analysis of Urhobo social and political systems. In fact, once one moves beyond the rather dramatic title of their book, they were fairly respectful of the term “clan.” They define Urhobo in terms of its clans, not kingdoms: “At present there are twenty-two clans in Urhoboland. Most of the clans are made up of groups of villages which trace their origin to a common ancestor” (p. 5). Similarly, they define the Ovie in terms of the clan: “The institution of clanheadship in Urhoboland is a most revered one. In some clans, the clan head is known as Ovie literally translated to be king” (p. 16).

Whatever Adjara III and Omokri intended to say in the pages of their book, it is the book’s title “Urhobo Kingdoms” that has won the day. Adjara III’s aristocratic colleagues have understood the book as recommending that the term clans be replaced by the apparently more appealing and more ponderous “kingdom.” And the Government of Delta State has readily adopted the new terminology, with consequences that are far removed from what any lovers of Urhobo history and culture will be pleased to accept.

Delta State Government’s “Creation” of an

Urhobo “Kingdom” and

Its Violation of Urhobo History and Culture

Throughout

the course

of Nigerian history, from the 1950s onwards at any rate, Nigerian

Governments

have accepted and then manipulated existing institutions of traditional

rulership. They operate in that way probably in order to seek advantage

for

their political parties and to please powerful individuals in those

parties. In

doing so, they have deposed opponents and installed supporters as

occupiers of

such existing traditional institutions of rulership. Some prominent

examples

will illustrate this point. In the 1950s, Ahmadu Bello’s Government of

Northern

Nigeria removed Emir Sanusi of Kano

from his throne and banished him from Kano Emirate. Similarly, in the

1950s

also, Obafemi Awolowo’s Government of Western Nigeria removed the

Alafin of Oyo

from his office and banished him from his realm. In the 1960s, at the

beginning

of the existence of Mid-West Region, Festus Okotie-Eboh orchestrated

the

removal of the reigning king of Itsekiri, his long-time opponent, and

facilitated the installation of a supporter of his as the new King of

Itsekiri.

In all these instances, previous Nigerian Governments accepted the traditions of the people and the institution of rulership that they mandated. What these previous Nigerian Governments did was to exploit the logic of these traditions by placing their supporters on the seats of traditional rulership, while removing their opponents. None of them defied the traditions of the people by creating new realms. The Government of Northern Nigeria did not split Kano up and place its own candidate on a fraction of the Kano Emirate. Western Nigeria Government did not divide Oyo up, in defiance of Yoruba traditions and history. Chief Festus Okotie-Eboh and the new Mid-West Government of 1964 did not split Itsekiri up and install their favourite candidate as king of one section. In previous instances of Government’s intervention in traditional affairs of kingship, the people’s traditions have been well respected.

In such respects, the conduct of Delta State Government in 2006 in splitting up Urhobo’s Idjerhe sub-culture and in creating a new “Kingdom” of Mosogar from the ancient territories of Idjerhe is unprecedented in the annals of Urhobo history and culture. Moreover, it would be difficult to find similar examples of the Government’s defiling of a people’s traditions elsewhere in Delta State. Let it be clearly stated at the onset here: Urhobo history and culture were severely violated in what appears to be the uncontested act of “creating” an Urhobo “kingdom” by Delta State Government in 2006.

The British had active and intense contacts with the Urhobo people for at least fifty years, for much of the first half of the 20th century. Although they came as colonizers, they nonetheless respected the integrity of Urhobo history and culture. They correctly identified Urhobo’s ancient sub-cultures and acted within their framework and logic. Similarly, the Action Group Government that took over from the British respected the traditions of the Urhobo people, despite historic difficulties between them and the political party that controlled the Government at that time. And it is fair to say that the Mid-West and Bendel State Governments were largely respectful of Urhobo traditions.

So why has this grave violation of Urhobo history and culture occurred in a governmental regime that has no standing quarrel with the Urhobo people? Two explanations have been offered by some Urhobo leaders who have bothered to discuss this matter. The first is that people in Government do not bother themselves with the creed of Urhobo history and culture. They say that some politicians would be surprised that any worries about Urhobo history and culture have been expressed. The second reason that has been suggested for permitting this brazen act of violation of Urhobo history and culture to occur is that the term “kingdoms” has become so trivialized that people in Government now believe that they can create them. As one Urhobo leader put it, “People in Asaba would hesitate to create ‘clans’ but not ‘kingdoms.’”

It must be noted that the Delta State Government has no Constitutional powers to create local governments in Delta State. Nor does it have the power to alter their boundaries. Why is it then possible that the Delta State House of Assembly can legislate on the existence and boundaries of Urhobo sub-cultures – call them clans or kingdoms, if these terms please? It has been said that this matter has been gazetted and that once matters appear in a Government Gazette, there is not much one can do. Well, Urhobos have a right to question the validity of a Gazette that violates their history and culture. In the long run, this whole cultural fiasco has very little to do with Idjerhe and its sub-units. The problem is that it strikes at the heart of Urhobo’s cultural existence.

Unforeseen and Untoward

Consequences of Delta

State’s

Creation of a “Kingdom” in Urhoboland

There are

numerous

reasons why the Urhobo people should be troubled by the spectre of

Delta State Government

taking over the control of Urhobo traditions, an instance of which was

the

so-called creation of a “kingdom” in Idjerhe sub-culture of Urhoboland.

We will

confine ourselves to only a few of these reasons.

First, the Idjerhe episode of “kingdom creation” is most likely to be imitated and repeated elsewhere – if it is allowed to survive. If every new installment of Delta State Government that comes to power has the right and authority to create “kingdoms” in Urhoboland, then we should expect a multiplicity of new “kingdoms” -- or “clans,” designating them by their other English label – to be created for Urhobos within several decades. There are everywhere short-sighted and ambitious politicians who will ask to be made kings of even small villages if the opportunity arises. Internal divisions within each of Urhobo’s sub-cultures may precipitate such clamour for kingship of new “kingdoms.” While there may be ready-made cases of divisions that will readily prompt any new Delta State Governments for new “kingdoms, the greater danger is that even the more stable and established instances of kingship in Urhoboland will not be safe from the spread of the cancer of Government’s “kingdom creation.”

Second, any increase in the number of Ivie in Urhoboland is a threat to the strength of our royal institutions. Many Urhobo leaders of thought already consider the twenty-two Ivie, who derive their authority from Urhobo culture, to be on the high side. It should be recalled that in the 1930s and 1940s, opinion leaders in Urhoboland and its Diaspora seriously weighed the option of initiating a single Urhobo kingship. If we cannot achieve such a goal, we must nevertheless not further weaken our circumstances by foolishly allowing the creation of artificial “kingdoms” in Urhoboland at the whim of Governments who may not always be well disposed towards the vibrancy of Urhobo cultural formations. The addition of a single Ovie to the system of twenty-two kings that we now have is a threat to our culture and to the dignity of those who currently occupy the thrones of Ivie in Urhoboland.

Concluding

Thoughts on Necessary Remedies

When the

Urhobo people

face a collective crisis, our usual resort is to ask Urhobo Progress

Union to intervene

on behalf of the Urhobo people. In our estimation, the Idjerhe episode

of

“kingdom creation” represents a crisis of a high level of disorder in

our

cultural existence as a people. We must rely on Urhobo Progress Union

to

persuade the factions in Idjerhe to do what all patriotic Urhobos do:

at the

end, the survival and welfare of our hard-won culture are important for

our

individual existence. What does it profit an Urhobo man if he becomes

an Ovie,

if by doing so he weakens the institution of Ovie? And what does it

profit any

Urhobo community if it gains a “kingdom” that leads to the downfall of

a system

for which all of our ancestors fought so hard? We trust that the UPU

will be

able to bring all the sections in Idjerhe together to settle what ought

to be

an internal problem.

On this score of persuasion, we also ask the UPU to apply gentle suasion on the Delta State Government to rescind its ill-advised “kingdom creation” exercise in Urhobo’s Idjerhe sub-culture and to kindly desist from any attempt to control Urhobo culture. It is not something that the Urhobo people should permit.

Finally, we appeal to Urhobo Progress Union to consider most seriously setting up a Committee that will study and recommend ways of regulating the titles that our kings and chieftains bear. It may be discovered, to the pleasure of us all, that there is no need to render Urhobo aristocratic titles in English at all. We are sure that this is a matter that will be of interest to the esteemed Kings of Urhoboland.

References

Adjara III, H.R.H.,

O.I. and

Omokri, A. 1997. Urhobo Kingdoms: Political and Social Systems.

Textflow

Ltd., Ibadan.

Edevbie, Onoawarie.

2007.

“Ownership of Colonial Warri.” Pp 233-257 in Peter P. Ekeh, editor, History of the Urhobo People of Niger Delta.

Lagos:

Urhobo

Historical Society, 2007.

Ekeh, Peter P.,

(2005). “A

Profile of Urhobo Culture.” Pp. 1-50 in Peter P. Ekeh, Studies

in

Urhobo

Culture. Buffalo, New York (USA)

&

Lagos, Nigeria: Urhobo Historical

Society.

Erivwo,

S.

U.

2003.

“The

Oghwoghwa Group of Group: Ogo, Ughele, Agbarha-Oto, and

Orogun.” Pp. 109-113 in Otite, Onigu, ed. The

Urhobo People. Shaneson C. I. Limited. Second Edition, 2003.

Foster,

Whitney.

1969.

African

Historical Studies 2(2):

289-305.

Reprinted in Peter P. Ekeh, editor, History

of the Urhobo People of Niger Delta. Lagos:

Urhobo Historical Society, 2007, pp. 37-50.

Moore, William A. 1936. History

of Itsekiri. London:

Frank

Cass

&

Co. 1970.

Otite

O.1973. Autonomy

and Dependence. The Urhobo Kingdom of Okpe in Modern Nigeria.

Evanston, Illinois:

Northwestern University Press.

Pereira, Duarte Pacheco.

C.1518. Esmeraldo De Situ Orbis. Translated and edited

by George H. T.

Kimble. London:

Hakluyt

Society.

Salubi, T. E. A.

1958. “The

Establishment of British Administration in Urhobo Country, 1891-1913.”

Reprinted in Peter P. Ekeh, editor, History

of the Urhobo People of Niger Delta. Lagos:

Urhobo Historical Society, 2007, pp. 67-85.

Salubi, T. E. A.

1965. President-General’s Address delivered by

Chief the Honourable T. E. A. SALUBI, O.B.E., M.H.A., President-General

of

Urhobo Progress Union, to the 16th Session of the Annual General

Council of the

Union held at Warri from Sunday, the 26th, to Thursday the 30th,

December,

1965.

Ukoli, F. M. A.

1998 [As

reprinted in 2007] “The Place of the Elite in Urhobo Leadership.” Pp

647-656 in

Peter P. Ekeh, editor, History of the

Urhobo People of Niger Delta. Lagos:

Urhobo Historical Society, 2007.

Notes

__________________________________

__________________________________

4 See Whitney Foster 1969 (as

reprinted in 2007: 41):

“Today one of the Isoko clans is Iyede.

Yet [William ] Moore

[1936: 13, 16] noted that Iyede was one of the four Sobo clans in the

Delta

prior to Ginuwa’s arrival. Upon

questioning two different groups of Iyede elders, two very different

stories

were obtained. One version can be

immediately rejected because of its political overtones.

The other states that the god, which they

still worship today at the site of their first stop in Isoko, was also

worshipped by Ogo, Agbaza, and Oghele.

These three names refer to the other three of the original four

clans

referred to by Moore.

Here,

certainly,

is

a good indication that at least one of the Isoko

clans of

today was an Sobo clan at the time [the Portuguese explorer] Pereira wrote [in

1518]."

6Thus, Salubi

(1958; as reprinted in 2007: 83) makes “a

reference to the role successfully played for many years by the wealthy

middlemen of the Coast in their two-way tactics of misrepresenting the

white-man, even including the Consul in some cases, to the Urhobo

people on the

one hand, and the Urhobo people to the white-man on the other. The

Urhobo

people were called all sorts of vicious names and described in a most

humiliating and discreditable way to the white-man and the outside

world. … But

the Protectorate Officers soon discovered the trick as will be

appreciated from

what Sir Ralph Moor himself said on the point. He said, the Consul had

been so

grossly misrepresented in the past by native traders and others, to

serve their

own ends, that his coming was greatly feared by the natives of the

interior.

The Consul's name had been used indiscriminately by the Coast traders

as a sort

of "bogey" with which to frighten the natives into compliance with

their wishes which were often of a nefarious character."

7

Other

names with “Urh” that the British could not handle and arbitrarily

changed to

versions with “S” include Urhiapele (changed to Sapele) and Urhonigbe

(changed

to Sonigbe).

8

The full

literal translation into English of “Ovie of Ughelli Kingdom” is: “King

of

Ughelli Kingdom."

No comments:

Post a Comment